Alice Frost, Director of Knowledge Exchange at Research England, reflects on a meeting between leading research commercialisation units from the US and UK, part of an enduring relationship between UK and USA Tech Transfer Offices.

Last week we welcomed visitors from America. This was part of a series of strategic transatlantic conversations that we have supported over the years between UK and USA university Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs). Organised by Dr Tony Raven, head of Cambridge Enterprise, we met with Lesley Millar-Nicholson, the head of technology transfer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Karin Immergluck, head at Stanford University, and Joe Allen who played an important policy role in the passing of the US Bayh-Dole Act and in developments on US university intellectual property (IP) since. (Bayh-Dole conferred ownership and obligation to exploit IP from federally funded research on universities in America.)

We heard from USA and UK experts on what we should do to advance commercialisation in the UK, focusing on the development of spin-off companies formed from university IP. This is one important component to delivery of the Government’s target of 2.4% of GDP to be spent on R&D in the UK.

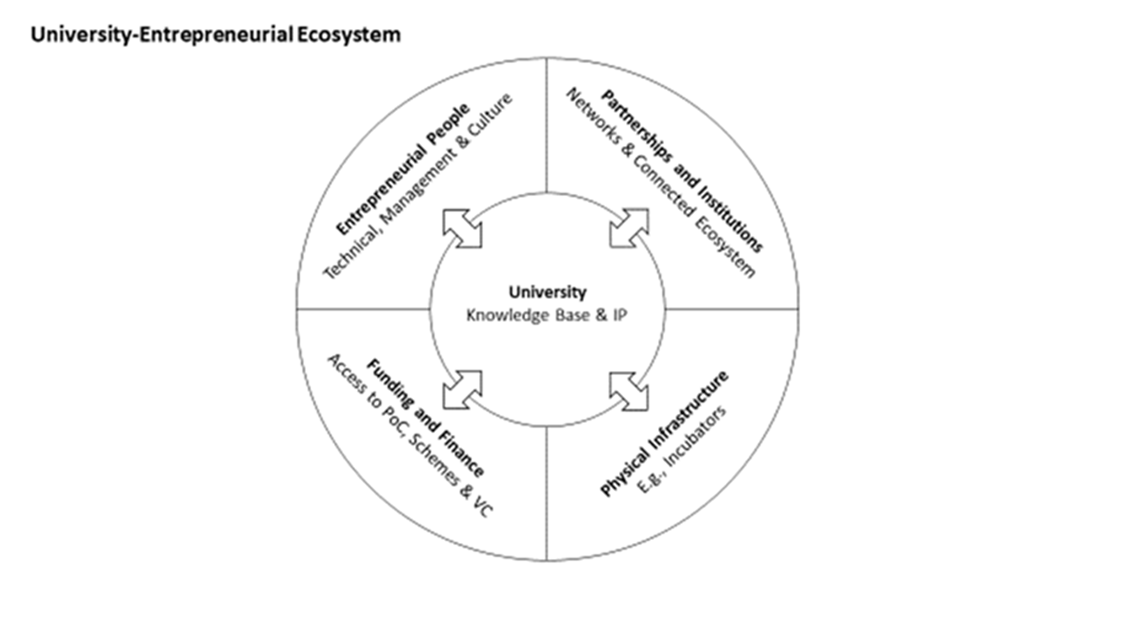

A key message was to reinforce the finding of the McMillan review of good practice in technology transfer (2016) that UK technology transfer now operates on a par with best practice in USA. It also confirmed the McMillan review conclusion that the “ecosystem” matters.

The entrepreneurial conditions in the surrounding environs to the university, such as access to venture capital and mentorship, affect how easy – or hard – it is to form and grow the very early stage tech companies emerging out of university research. This in turn affects the role played by technology transfer experts.

In Kendall Square around MIT, or in Silicon Valley around Stanford, the university TTO focusses on the licensing of the technology, with the ecosystem naturally supplying the other ingredients to start up. The university and particularly the TTO may play little part in spin off formation, with the faculty member able to find the necessary resources and expertise in local, private partners. Academic faculty may then turn up in the TTO with venture capital and a management team already on board, just wanting a license from the TTO to use the university’s IP. (We learnt though that licensing in a university of the scale of MIT is a mammoth and fascinating task. Challenges include the increasingly team nature of research with IP then owned by multiple inventors, a myriad of potential conflicts of interest where faculty are entrepreneurs and ethical and practical challenges of exploiting new technologies like Artificial Intelligence.)

Our conversations though turned primarily to the experiences of universities outside of these globally leading ecosystems. Although the Cambridge cluster is much admired worldwide, Tony Raven confirmed that at Cambridge, venture capitalists do not beat down his door daily. In terms of experiences of other universities in the UK, we noted, as an example, that venture capital in the North East of England totaled £1 million in 2017 out of a UK total of £463 million.

We then learnt a lot from Lesley Millar-Nicholson’s account of her previous experience at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She took us through the journey of a university with no existing ecosystem but with research to exploit. In a “fly-over state” between the successful West and East tech and finance systems, persuading a venture capitalist to drive the two hours out of Chicago was an almost impossible task - initially. The word “bootstrapping” was used to describe the process of gathering resources for incubators, accelerators, entrepreneurship programmes and the like, toward a successful commercialization offer and environment.

The inspiring feature from our conversations was to realise the important role that a university can play in local economic development, helping places and communities benefit in the transition to a technology and knowledge-based economy. Universities play a critical role in the inter-section of national UK policies on commercialization and place, helping ensure that the whole country benefits from our world class research and innovation.

It was timely then that this week we also launched a competition to allocate £10 million from Government and our Research England Development Fund for development of incubators and accelerators, as part of the Government’s University Enterprise Zones (UEZ) programme. This builds on universities’ strong commitment in this area, with over 120 English HEIs reporting access to an incubator or acceleration offer. However, quality in incubation and acceleration is the critical factor, to achieve intended outcomes such as faster growth and increased access to finance for tenant companies. The UEZ programme is a very important opportunity to identify and spread best practice, and we look forward to working with university experts to deliver this.